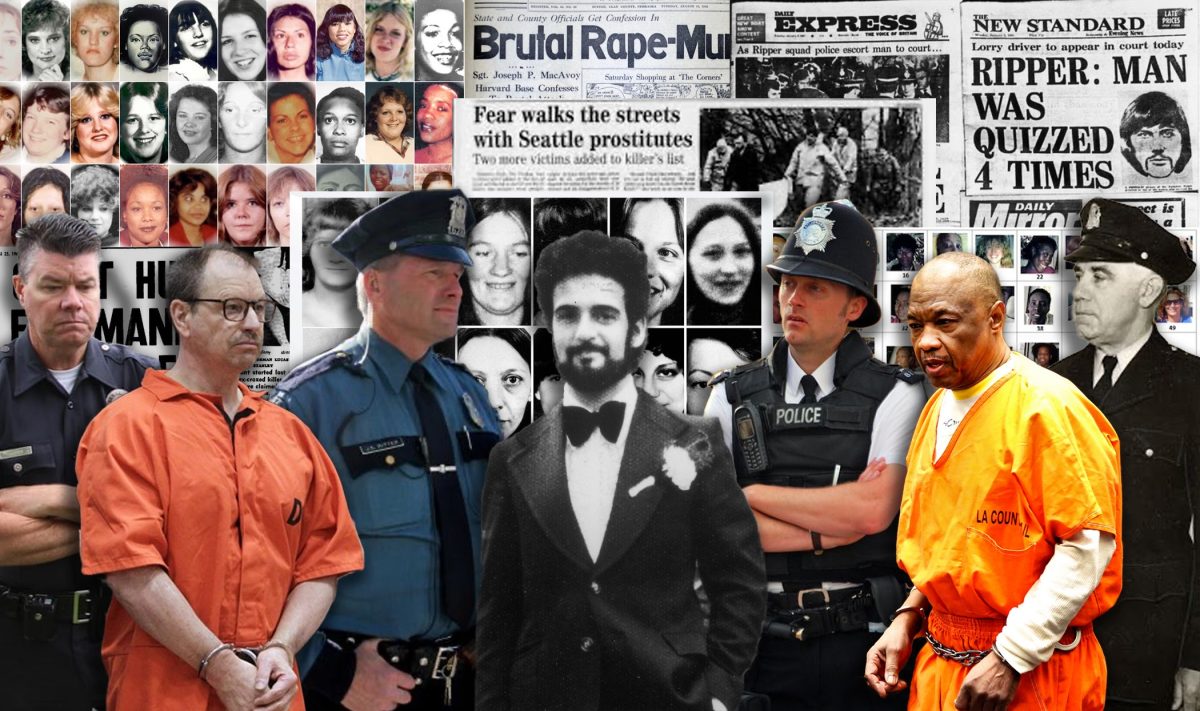

Photo illustration courtesy of junior Linnaea Marks.

True crime films, series, and podcasts are popular amongst SLOHS students and have become ubiquitous across streaming services everywhere. An abundance of serial killer docu series available to the public has highlighted some serious negligence on behalf of the police in solving these cases: forced confessions leading to wrongful convictions, gaslighting, and willful disregard of suspects have led people to deeply question the moral compass of the criminal investigators they were led to trust.

Through all the true crime documentaries, one of the many apparent flaws in the legal system is the blatant misogyny and lack of female perspective in investigations, especially those that involve rape and crimes against women. While sexism was somewhat abundant among all fields of work leading up to today, it specifically jeopardized women’s safety for female police, lawmakers, and press workers to be underrepresented and for the voices of victims to remain unheard.

As criminal justice teacher Curtis Bartlett explained, “things that are today classified as rape were not as recently as 40 years ago. In fact, the F.B.I. did not recognize certain rapes until about 10 years ago as rape.” He added that “the lack of women on police forces, I think, did have the effect of manpower not being allocated to these crimes.” With more female lawmakers, it’s possible that rape would have been considered a more severe crime sooner.

One case that exemplifies misogyny in the British government is that of the Yorkshire Ripper. Various government officials during the case suggested enforcing a curfew on women in the cities the murders were occurring. Bartlett said “a curfew for one group of adults is blatantly wrong in my view. The government should warn people of the dangers and let them decide.” The curfew infringes upon people’s civil liberties regardless of gender, but to enforce it strictly on women is blatantly sexist.

Additionally, sensationalization from the press labeling female victims as “prostitutes” was a regular practice, one that according to Bartlett “certainly can lead to a false sense of security.” Bartlett advised that “ALL people should be cautious and live in a yellow zone of caution.”

In the Yorkshire Ripper case, because the killer targeted women in red light, low income districts who were walking alone at night the press diagnosed him as a prostitute killer, and police asserted that women who weren’t prostitutes shouldn’t worry about attacks.

Sure enough, within a matter of weeks, he murdered a young girl not affiliated with any illicit activity. Some of his first surviving victims who were ignored by the press asserted that many of them weren’t prostitutes at all, and the press mislabeling the victims was potentially dangerous for other women.

The same sensationalization occurred over a century before during the Jack the Ripper case and on many other occasions.

Even in cases where prostitutes were the only targeted victims, such as that of the Green River killer in Washington, misogyny over the general population caused an indifference to the murders of these young women. Gary Leon Ridgeway confessed to the murder of 71 women and girls and was convicted of 49 murders, one of the highest numbers in American history. A contributing factor in his ability to be actively murdering for so long a time is the public’s lack of compassion for people identified as “prostitutes”.

The Grim Sleeper case in Los Angeles displayed a similar disregard of the lives of women living in a low income neighborhood. For 25 years Lonnie Franklin’s murders went undetected because his victims were women of color in South Central Los Angeles, one of the poorest neighborhoods in LA. Had these women been wealthy or white or high profile, the case likely would have been solved more urgently because of pressure from the public.

After researching the cases of numerous serial killers, it’s obvious that misogyny has a deep impact on these investigations, from police negligence to sexist laws to an overall indifference from the public to protect certain kinds of women.

Today, as Bartlett states, “victims now have advocates and sympathetic ears, which gives the police more evidence since it is easier for the victims to open up.” So while misogyny in these cases is generally on the decline, it’s still important to stand in solidarity with victims of all genders and destigmatize being a victim of these crimes and attacks.